As the world is sheltering in place to avoid Covid-19, my grandmother’s letters take on a new meaning. I better understand her boredom, listlessness, paralysis, and general apathy.

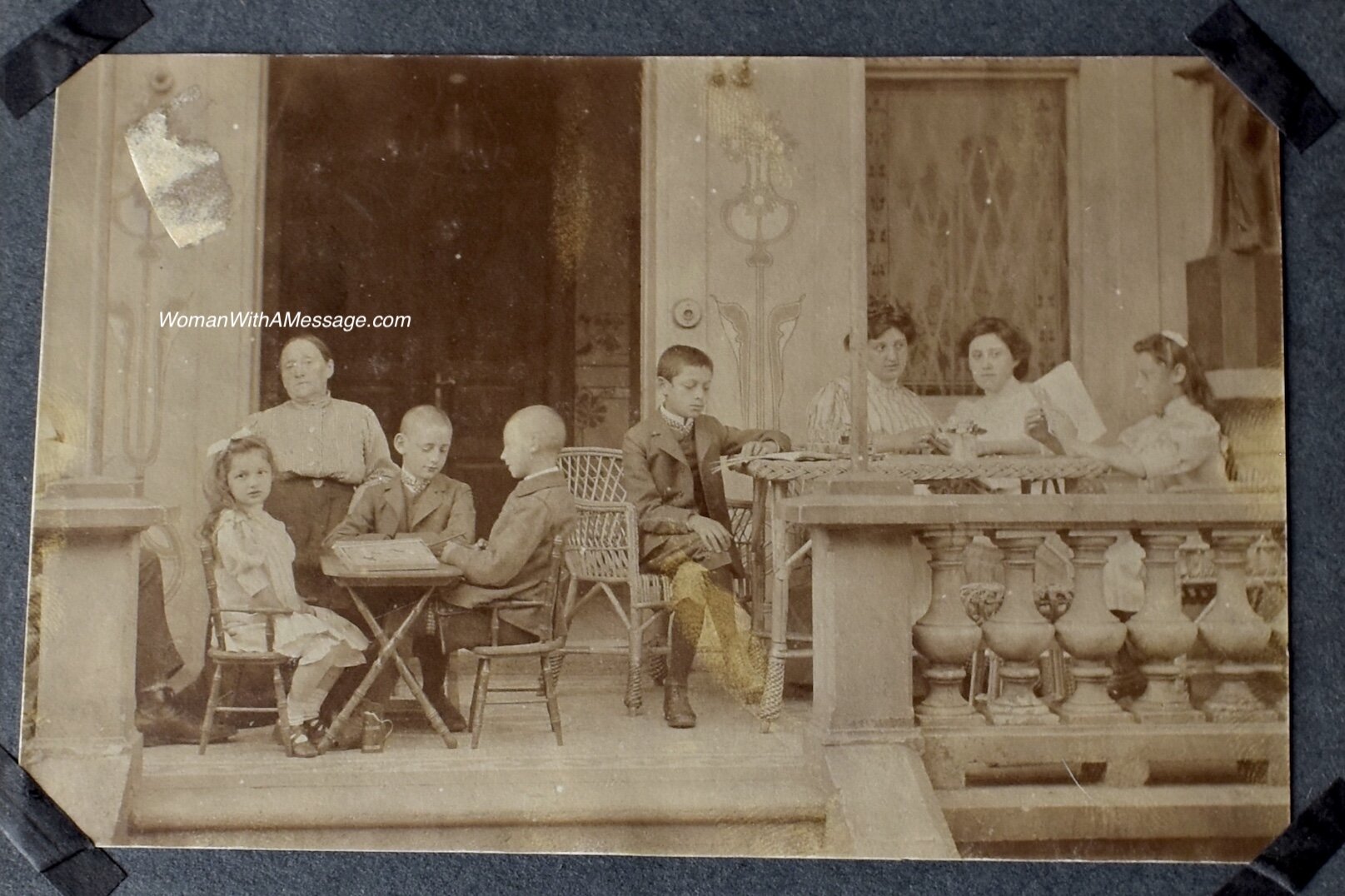

By the time Helene’s children left for San Francisco, life had become very difficult for Helene and Vitali. They had very little money and apparently were not allowed to work much. In the early months, they went to the movies from time to time, mostly to watch the Newsreels in the hopes of seeing California and imagining where their children were living. Their stationery shop was open for limited hours, and a handful of customers came in to buy postcards and pencil sharpeners, but certainly not enough to pay the bills. They lived on credit, while hoping to get passports and travel documents to travel to the U.S. They sold what furniture they could and burned the rest of it to keep warm during the bitter cold winter of 1939-1940. They often wore all of their clothing in layers to keep warm, even in the house. Helene spent most of her time at home, writing letters and waiting by the window watching for the to postman arrive. They ate sparingly but joked about the bounty of their feasting.

Here are excerpts from a handful of letters:

On missing her children:

5 December 1939

There was a shoot ‘em up film being shown and since it was about the construction of the pacific railway, we went in. Harry would be very surprised because we don’t like things about shooting anymore. But at the end, when the train in its current form hurried across the movie screen, my heart stopped for just a few seconds and I thought that my children were just recently sitting in such a monster of steel and iron.

The truth is that I feel old as the hills and I feel like a hen would feel if she were hatching duck eggs and I am clucking. When the young ones go to the water and happily swim away from her for the first time she probably can’t believe her eyes in that situation. But I’m an intelligent hen, and even if I do cluck sometimes, I am happy to know that you are with people who are good and noble.

——-

December 29, 1939

What do you say about the terrible earthquake in Anatolia? I am quite worried about the consequences of this catastrophe. Because Casablanca and Los Angeles are in the same meridian, I would be happy if this catastrophic year were over. Thank God it’s getting there.

—-

March 12, 1940 to Harry

We just got your Christmas letters and it took 100 days to get here but were still so happy to get them.

….

I can imagine what you are doing and sometimes I don’t factually know if you’ve really written this or if I just imagined something. Then I take the folder with your letters into my hand and I read your letters over and over again. Sometimes by taking a letter for example from January 18th and then the next week I get one from October 21, I entertain myself and it’s like playing with a mosaic or puzzle. Every card is a new piece and the picture becomes ever more complete. I wish I had more pieces and maybe the mail will bring me greetings from more recent times in the next few days.

——-

April 4, 1940

Sometimes it is to me just as if the children had stayed just a little longer at school. The few weeks which children went to a sort of summer camp during school vacation seemed longer to me than the current separation. But back then, one had the wish or at least the possibility to amuse oneself. But this is not always true. Then there are days, usually when there is no mail, when everything seems twice as hard and difficult and one thinks about 3 times as many. A heavy sleep is like a narcotic. Then, after such a nirvana, when the mailman rings the bell and actually does bring a letter from you, then I take a deep breath and my limbs firm themselves up. It becomes a delight to do the dishes, and my fantasy has received new wings during cleaning.

——-

July 19, 1940

Meals are the best time for celebrating reminiscences and thinking about you. We were in fact just at table for a meal in the greatest of moods. When I’m spreading butter on my bread, Vitali says “your son would have been able to use that much butter on 14 pieces of bread” (14! think of it). And if I put sugar in my tea he says “you eat too much, you’re getting too fat. Why don’t you use your daughter as an example?” And with such sentimental jokes, we pass the time and breakfast.

On the bitter cold winter:

December 29, 1939

…. it is not childish to be happy that you won’t have to walk around with red ears and a blue nose.

——-

January 2, 1940

….The old year just wouldn’t go away. It was a bad year and did bad things to us. Its parting gift was Siberian cold. Imagine the temperature in our kitchen. I decided to make a party goulash. The onions I kept in the kitchen were so frozen that they looked like balls of onyx. I was angry that I had to destroy their beauty with my knife. When I cut them up they acted like broken glass breaking into atoms. My fingers were fascinated by this and decided to show off a dark coral red which changed to ruby red. My fingernails were shining like violet amethyst. It was a piece of degenerate art.

——-

February 17, 1940

I don’t know why it’s not considered proper form to write about the weather and it shows you have an intellectual poverty if you do something so mundane as to write about the weather. I don’t find that there’s anything that changes more than the weather. After we had a few days of normal winter temperatures, it was -5 even in the sun. Fingers while playing musical accompaniment were even able to do a few knee bends. Then the weather went downhill again. My limbs felt that new cold and became stiff again. All the clothes I wear in the kitchen, I look like something out of a fairy tale - sort of a combination of Red Riding Hood and a witch, but really more on the side of the witch. With Papa I have finished a certain signal. If I leave after we eat soup and don’t come back until the second course we might have, then he should come looking for me, although I haven’t turned into a pillar of salt like Lot’s wife but I probably have turned into an icicle.

….What a Viennese person cannot understand. Papa is wearing a coat and not hanging it over his arm. When he is going shopping, the Vienna women let him go first because they worry about a man who does not have a winter coat….

——-

February 22, 1940

On the 18th, I wanted to send my letter from the day before and decided before that to make a nice atmosphere. So I got an arm chair, a leg of an armchair, an old sofa pillow and a couple of coat racks and a few shoe stretchers for both men and women. It didn’t exactly get warm. The coal deliverer had left us hanging. But Papa decided that I would be a pyromaniac. While I was trying to have a little talk with our oven, I was trying to explain that a reasonable oven would realize there was no coal there, but it could eat something else. Our oven did not listen to reason. It made noise. The house manager said that the pipes had burst because of the SIberian cold so we had no water in the kitchen. That wasn’t so bad, we at least could use the phone and bathroom. …

_____

8 March 1940 from Vienna to Harry

…. At least its still a little warmer. I took off my third pair of stockings and am only wearing two pair now, one from rubber and one from a wool-like substance….

——-

April 13, 1940

In actuality, the thermometer was -1 degree today and our oven is fed with all sorts of goodies. He is currently eating the ruins of an armchair which I found when I was cleaning out our basement. The latter I had to clean out because it’s going to be commissioned as a bunker…..

On whiling away the hours:

January 29, 1940

There is not really much to say about us. I leave the house twice a week to go shopping; and the daily needs such as bread and skimmed milk, Vitali takes care of that, because he has to do something new with his original business hours.

….

Vitali has been forbidden to undertake any kind of activity.

_____

March 19, 1940 from Vienna to Paul

If I were to give you a description of our days you could be forbidden to fish because you are yawning so much. So I see that I will just assure you that it’s not an easy task to go from being quite busy to being forced to do nothing. Well, doing nothing is not quite the right expression because my time is really taken up with cooking, washing the dishes and the laundry, straightening up, and other kinds of housework. But, however I have enough leisure during these activities to think about a lot of things. This thinking is what reminds me in a painful way that in our matter we must take consciousness of our situation. Then however there’s the matter of the mail dragging along and that just makes me have dark thoughts. But I don’t want to foist off my melancholy mood on you. It goes away as soon as I get one of those letters that’s on the way.

——-

August 2, 1940

To be condemned to such passivity is a very unpleasant thing and harder to learn than any other subject you might study. So I’m doing some remedial work on what I didn’t had time to do over the past few years and I am reading a great deal. My intellectual pursuits are with Leonardo, Michelangelo, Machiavelli, and their contemporaries. As you see I am living in the deepest Middle Ages. Papa is doing the same thing, but the difference for him is that he has done this for years and I’m more like someone just starting school. I really had to figure out how to hold a book. It’s a lot harder to read when you hold the book upside down in your hand. The weather of the last week was so unfriendly that I preferred to stay home and can vegetables for the winter. Vitali was very industrious in helping me because you can’t just read all the time. So with these two completely different activities - one for the mind and one not - I am perhaps more inclined toward the last. At least you have a way to leave your thoughts free and the thoughts come right to you. The day before yesterday I promised my mother in a dream that I would not leave her behind and that I would stay here. In the morning I regretted my premature promise.

On having little money or food:

December 8, 1939

Its winter in Vienna, cold and snow. We don't have much to spend on food and such but we are lucky that we do have a card that allows us to buy clothing, wool. We can also buy vegetables close by. I’m not used to going out, as you can maybe tell. I take the garbage out and shop at same time so that I only have to go out once. I forgot my grocery card and got angry at myself. Wanted to buy something without coupons but realized I didn't have my shopping bag, but the garbage bag.

When we go out, Papa now says “Helene, did you remember the garbage bag?” Here I am just writing about garbage bags, reflecting my mood. ….

———

December 14, 1939

Our stomachs are used to not getting such goodies anymore.

Papa has a sour grapes philosophy – we ate too much anyway. Maybe he’s right, but it sure would be nice to have something/it was nice to have it.

——-

January 29, 1940

The sale of unnecessary objects is how we are paying for our expenses.

—-

March 12, 1940

Papa. He came with such an expression of a poor sinner that I had to laugh. I’d already forgotten about the soup but Papa thought he should make it up to me and brought a splendid Baltic Sea herring with him. We felt like we had a meal of the gods.

——-

March 19, 1940

Yesterday I wanted to go to procure for E&H Lowell [Eva and Harry] some shaving cream for papa for March 21 [his birthday] but our account was overdrawn. We have an advance until July and so can’t really buy anything.

On imagining leaving Vienna and creating a life in the U.S.:

March 1, 1940

….

About 2 years ago in a beekeeper newspaper there was a notice that California needed beekeepers. Please let us know if this is true and if the lack of beekeepers is still of current concern.

——-

8 March 1940

Tonight the king of Iraq gave us passports so we could visit you. Unfortunately, that was just a dream and he’s dead anyway and his resurrection is fairly unlikely.

——-

March 26, 1940 to Harry

There was a man from the air command here looking at our apartment because we have received notice that we will have to leave the apartment soon. Papa acknowledged that we received that notice but that we are not at the present time thinking of giving up our apartment. How much I would like to since so many people have shown interest in seeing us elsewhere and maybe will help us to figure that out.

_____

March 26, 1940 to Paul

Soon you will have regained your independence and achieved a sphere of influence appropriate to your enthusiasm and knowledge. In a country where you are still in the process of learning the language for practical use, it may take a bit longer. I am reminded of what an acquaintance, who now lives in London, once told me: “What good is it that I can read Wilde or Galsworthy in the original, but I don’t know how to say ‘rain gutter’?” We looked it up right after that, but I don’t think this knowledge would really help me make progress in the USA. I only wish I knew if it would serve any purpose for me to learn Turkish, Chinese, Spanish or English. But what does a goose dream about? Just about corn. (something is wrong about that word, but I don’t know what). So I dream about reuniting with my children. While I work with a broom and duster, I wander through California’s blessed fields with you.

——-

April 13, 1940

On my birthday and Christmas I got from Papa some stockings as well. He used the points he had available and I think a friend of mine may have helped him out with additional points. I am not wearing them however, I am saving them for my daughter. …