Link to Family Tree to understand family relationships.

Istanbul, 2 March 46

Everli, my golden Everli!

Isn’t it strange that I got the first letter from you on the anniversary of my “liberation?” Here it is winter. We have the wonderful show that nature puts on to watch. Within 24 hours all four seasons with their advantages and disadvantages - that’s what we experience here. It’s a spring day. Almond trees and other trees and bushes whose names are not known to me are blooming. Around mid-day the sun was beating down with such intensity like in the middle of summer. Suddenly, some dark clouds came up. At first this looked like it would bring a cooling summer rain, but gradually there were mixed in with the raindrops little pieces of hail and then snowflakes. So strange - they were so big that you would think it was Hollywood (one or two “l”s?) just finishing up a guest performance in Istanbul. The night was icy cold and I was freezing in my little room which cannot be heated. I was under two heavy blankets and I was pitiful in that situation. I did what I always criticized Vitali for when he did it - I put my coat and all of my clothes over my feet. When I woke up in the morning and wanted to change my embryonic state, I saw the most splendid winter landscape that I had ever seen in my life. Palm trees, magnolias, almond trees, and laurel trees were covered with snow. A blue sky and the sun was going up like a red balloon. The snow disappeared incredibly fast from the trees and bushes. The sun looked golden and I opened the window which I had so fearfully closed. It was singing in me: Winter storms make way for the moon of delight [does some wordplay with “Unwalkürlich” play on Unwillkürlich/Walküre - involuntarily]. The large amounts of snow metamorphosed into ponds. The paths were impassable. I think the god of weather wanted to make an impression on me and pulled out all the stops. The Lodos [strong south-westerly wind, like the Mistral in southern France and the Santa Anas in southern California] paraded with the trees, having them do knee bends until the ponds disappeared and the dirt on the streets looked like mountains of mud. It led me to believe that there would be a new summer afternoon. It’s cold again, it’s raining. The oven in the day room is eating up forests of wood. Around the oven, people are sitting and letting themselves be baked. I am not cold, I’m warm and I have the sun in my heart since yesterday. But your long letter did not completely satisfy me. I am dying to know about my son, your husband. I want to know more about him than just his name. I don’t share your fear that a description could be too conceited. You could have tried to say something negative about him. This is the first and I swear the last mother-in-law advice that I have given you. There is nothing else I can do besides follow your advice and form my own judgement about this.

The day before yesterday I found out about your money transmission (100 lire) which I’m very grateful for. As much as cousin Yomtov has taken on my case and has declared himself ready to pay for the costs of my boat crossing, the Joint committee would not take payment in lire and insisted that payment had to be made in dollars. Here too he could have found a way, but the Joint insisted on the dollar transmission, although thousands and thousands of people have managed to be sent to their country of destination without even paying a penny. I will get to the bottom of this thing as soon as I am over there with you. I have to go now. In a half hour we can’t have any more lights burning. Be well my little bunny. Good night. Soon I will feel your good night kiss, not just in my dreams.

Your Mutti

——-

[In English]

My dear Ludwig,

Many thanks for your kind lines and the courage you have given to me. The very thought to be able to live with and for you makes me happy and I hope never to be a stumbling-stone in your happiness. You quoted a sentence by Voltaire I had not known and I found it very true. I remember another from him about Rousseau: “Poor Rousseau should have a blood transfusion, for his own blood is a mixture of arsenic and vitriol. He is the most unhappy human being because he is the most evil.” Does this quotation not much more fit to Hitler? By and by I feel reconciled with my fate. What it took away from me, it gave to my children. Eva her husband, Harry his independence. I thank you for your effort to look out for a bigger place and I assure you I will endeavor to keep your home well as long as you want it. Although I am only a shadow of my own self I wish to be helpful if not even to you but to your children. I am the fairy tale grandmother devoured by the greedy world. Do you know another grandmother who can tell her grandchild this adventure with more authority? Just now I am not afraid by the big bad wolf and you must not fear I will amuse your little son or daughter with the description of the bad digestion of the poor voracious animal.

My dear Ludwig, you have taken from us one of the two most valuable things we possess and still I am not cross with you. It is funny, is it not? Please ask your wife to translate my first little letter into a correct English. I hope to hear from you very soon, but I should prefer to see you personally much sooner.

Love,

Helen

Again we have a letter rich with imagery, detail, and enough information to help us understand Helene’s life in Istanbul. She mentions her “liberation” in quotation marks, because although she was no longer a prisoner in Ravensbrück, for her the past year has been a different kind of imprisonment. She gratefully writes of Vitali’s relative Yomtov who has been working to help Helene get the money and paperwork to go to San Francisco. We saw some of Yomtov’s letters in January.

Winter in Istanbul is very different from Vienna, but Helene suffers some of the same hardship. Her residence is poorly heated and she does not have enough blankets or clothing to keep warm. The Lodos are strong south-westerly winds, much like the Mistral in southern France or the Santa Anas in southern California. Even after all she’s been through, she continues to use humor and word play, keeping as light a tone as possible. She is trying not to sound depressed and heartbroken – at her experience in Ravensbrück, at losing Vitali, at the lost years seeing her children grow up, at losing her beloved Vienna, and now at the sorrow of not having been by her daughter’s side for her wedding.

Eva apparently shared little about her husband, including a key detail that he originally was from Germany and was fluent in German. So Helene struggles to say grateful and kind words to him in English.

It is a bit disorienting for me to read her note to Ludwig, my father. She writes of telling stories to her grandchild. I am that grandchild. I don’t know if she ever told me about the fairy tale big bad wolf or the real one she personally experienced. All I remember is a woman who was sweet, loving, and kind — despite the hell she had experienced.

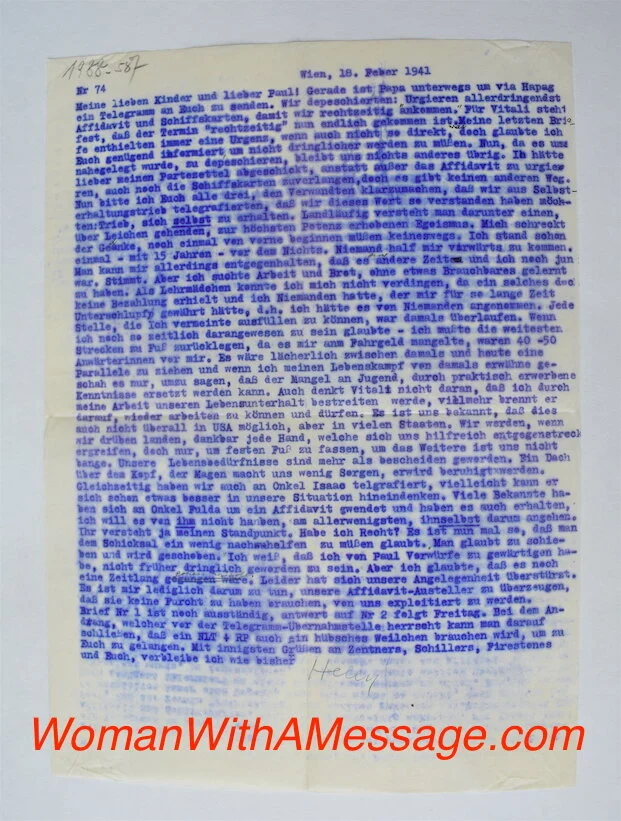

Helene will finally be reunited with her children in a few months. Here is a photo probably taken later that year. Although a bit blurry, it is nice to see Helene looking so happy after all she’s been through.

Helene, Harry, Eva, Ludwig